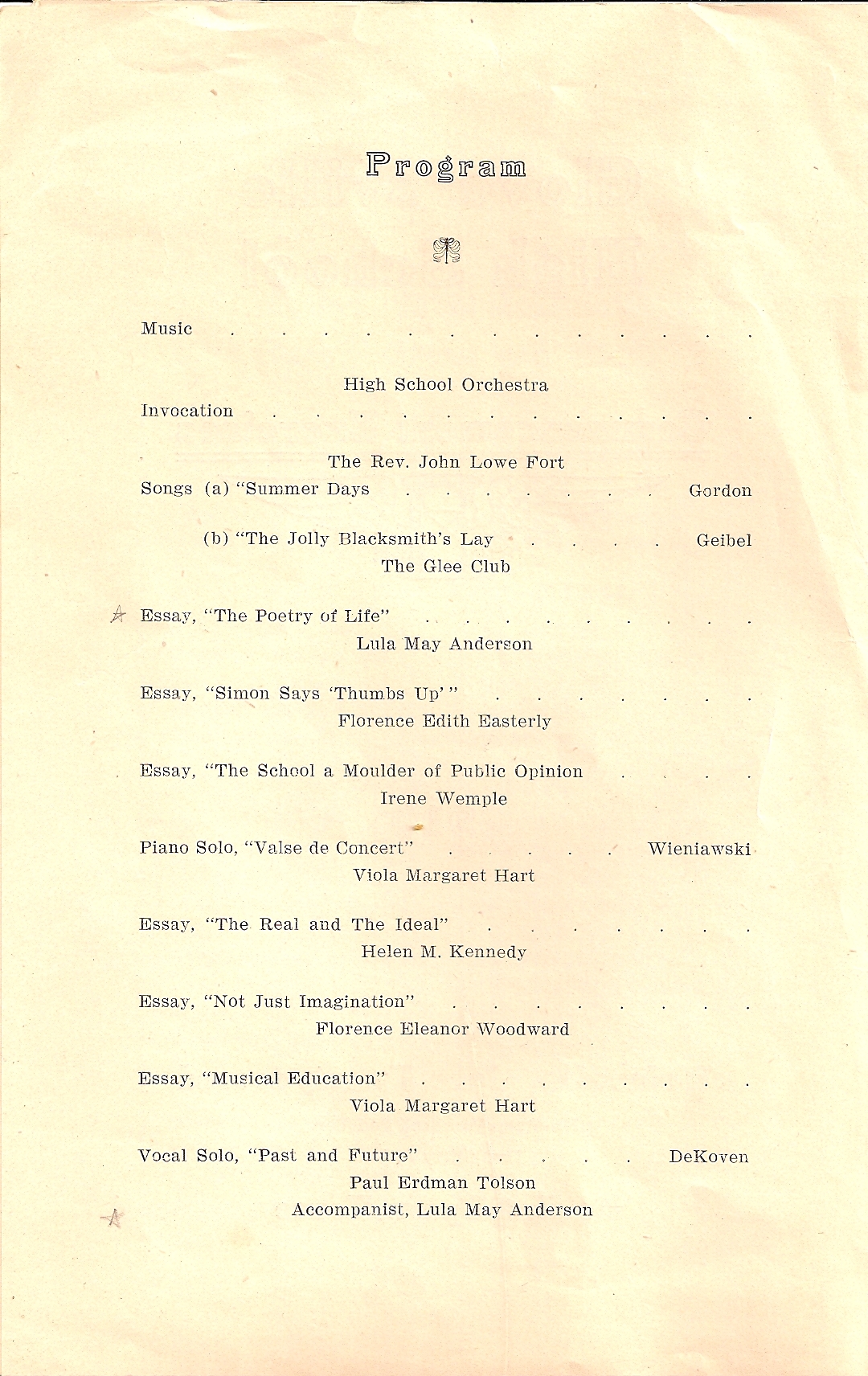

This is the high school valedictorian speech Lula M. Anderson (Robison) wrote and presented in 1910, Gloversville, New York.

It was while heads were bent over books, and minds were intent upon lessons, that Poetry stole softly in upon us. She was so very quiet that we did not see her at first, but still we felt her presence. The very atmosphere seemed changed; the restless became earnest, the mischievous became thoughtful, and all anxieties disappeared. Her very countenance bespoke Peace, and when she spoke, we heard a voice most musical.

Of course, there were some who did not recognize the Muse, nor even heed her voice, but these did not realize their loss. She had come to inspire those who had learned to love her works. Her gaze seemed to pierce through our very souls, yet we did not shrink from it, for she stirred our better feelings, and moved us with her words. Sometimes we laughed with her; sometimes we wept, and then again, we were set to thinking deeply. Truly, this spirit had a strange power over our emotions, and yet we were glad to be in her power.

Before the arrival of Poetry, we had been discontented and ill-satisfied with our lives. All things had seemed so commonplace that we could see no beauty in them. But now things looked brighter, and as though a veil had been lifted from our eyes, we began to see clearly the beauties of our everyday surroundings. Although the Muse left us quite as suddenly as she came, there is one teaching that must remain with us, and that is, "Find the ideal in the real - be a true poet, for he alone can catch life's rhythm."

Life is not entirely prosaic, if it were, it would not be worth the living. It is not all work with no play, there is a sufficiency of fun for all in this world, good, wholesome fun. It often comes to us when we least expect it, as we are on our daily rounds. If we are not too narrow to see it, we must appreciate it, for there is inborn in each of us, a sense of humor by which comes the greater part of life's pleasure. I do not mean that fun is the aim of life, or that it will last forever, yet there are times when a little merriment helps over the hard places, and smooths the way before us. But perhaps as we grow older, we would have our pleasure in something more certain. And this is not wanting either, for the best things in life are boundless. The rain, the sunshine, and the very air we breathe, were created for all, the rich and poor alike, and the beauties of Nature are for all who would see them.

If life is not prosaic, it must be poetical, which it truly is. As long as there exists love and truth, so long there is Poetry in life. As long as the patriot will lay down his life for his country, or as the mother will sacrifice for her child, the poetic feeling is not lost. It was Lowell who penned the lines:

"God scatters love on every side,

Freely among his children all,

And always hearts are lying open wide

Wherein some grains may fall."

To find the Poetry of life, we must have, first of all, an eye to observe accurately, and a sensibility to feel deeply. Then we need the power of imagination, and lastly, an ear attuned to the music of Nature. Everyone, even the most uncultured has these qualities in a greater or lesser degree. Perhaps the one which we sometimes overlook, is imagination. We often come in contact with persons in whom we think there is not one spark of imagination, yet sooner or later, we find that we have been mistaken, and that there is, after all. Everyman has before him a vision of the future, in which he sees himself as master. At the plow, he looks out over the fields of grain and imagines himself the owner of the broad acres, stretching far and wide. At the bench, he forgets the shoe he is working on, forgets the presence of his fellow - laborers in the stuffy little room, while thinking of the time when he shall be at the head of a great factory, a master of men. Then too, in the small attic room, where struggles the artist or the student, imagination is not wanting, for each cherishes a secret hope that his work shall become a masterpiece. And so, having seen the power of imagination, it is for us to use it to bring Poetry to our lives.

There are those who see only the hard crust of reality, who feel only the cold side of the world, and who hear only the discords of life, but these must have forgotten that the sun does not cease to shine when clouds o'erspread his face. And we would have them remember also that just as the sun will break through the darkness, and dispel all gloom, just so the ideal is behind the real, ready to burst forth in a glorious horizon, if only we are willing to let go the clouds of discontent. It has been truly said that there is in Nature, just as much, or as little, as the soul of each can see in her. To the dull, mechanic mind, this marvelous earth is but a black ball of mud, painted here and there with streaks of gold. But to the true poet, the earth and sky have not lost their original brightness. Everything in Nature has a wonderful charm for him, from the lowliest flower, to the most glorious sunset, while the very heavens above him seem no bluer than the tiny harebell growing by the wayside.

Perhaps you are thinking that all have not the chance to see the beauties of which we speak. You say, "Only think of the thousands of poverty-stricken lives in the crowded cities, deprived of the very necessities of life, even of light and air. Surely there can be no Poetry in such lives?" True, there are many who do not receive the blessings which Nature meant for all her children. Whose fault is it that they are thus? We cannot say, but at any rate, we do not believe that their lives are entirely darkened. take for example, this mother who has toiled hard all day to put the bread into the mouths of her little ones. Where is her Poetry? It is after the work is done, and she is in her little home, holding tight her baby in her arms and crooning it to sleep. She will tell you that then come her happiest moments and her fondest dreams, joys which to the mother compensate for all hardships. But let us turn to that group of ill-clad waifs playing in yonder alley. We look at them in pity, yet they do not want our sympathy, for they are happy. Ask them if they are having a good time, and if they are not too impudent, they will answer, "Yes." But see, here comes a feeble old man tottering down the street, leaning heavily on his cane. He has lost the vigour of his youth, and is patiently waiting for the end, yet he too has not forgotten the music of other days. "Don't ever think that Poetry is dead in an old man because his forehead is wrinkled, or that his manhood has left him when his hand trembles!" said Holmes. If then, poverty-stricken toil, neglected childhood, and old age, helpless and infirm, can yet share the sweetness of life, are there any so narrow that will deny its presence?